In the midst of economic calamity and the pandemic, capitalism is under fire. Present important debates over inequality of opportunity and outcomes, reinvigorating communities and addressing challenges from globalization to climate change to broader social justice come together in questions about our economic system: What should businesses and their leaders be doing? For whom should the corporation be run? The shareholder primacy viewpoint — espoused by Milton Freidman exactly 50 years ago in The New York Times Sunday Magazine — argues for maximizing the company's long-term value, while conforming with the laws of the land.

Last year, the Business Roundtable embraced a new paradigm for corporate objectives — stakeholder corporate governance that proposes a commitment to customers, employees, suppliers, communities in which the corporation operates and long-term shareholder value. The stakeholder paradigm suffers from internal inconsistencies. Recently, GM closed several auto plants manufacturing gasoline/diesel vehicles in Michigan and Ohio, laying off thousands of workers. These plants were later retrofitted to manufacture electric vehicles but employed many fewer workers. How should General Motors (GM) managers consider the trade-off between jobs and environment-friendly vehicles, if not for the underlying discipline of long-term shareholder value?

| Read more “Two Views”… |

Another practical challenge of the stakeholder governance paradigm is the measurement of that commitment. Under the stakeholder paradigm, almost any management expenditure of corporate resources, short of outright fraud, can be justified as addressing the priorities of some stakeholder group. Hence, the lack of managerial accountability becomes a problem.

The stakeholder paradigm assumes that shareholder value maximization will have an adverse impact on the other stakeholders. For example, managers will not compensate their employees fairly or treat them respectfully. However, employees who are unfairly treated have avenues of redress. In a competitive labor market, the employee can resign and seek alternative employment. If the labor market for the particular employee is not very competitive, or if the search and moving costs are very high, the employee can seek redress via litigation or regulatory relief. Managers, aware of the employees' redress options, are less likely to treat the employees unfairly. Similarly, in a competitive product market, companies have to provide their customers with value, else they will lose them to the competition.

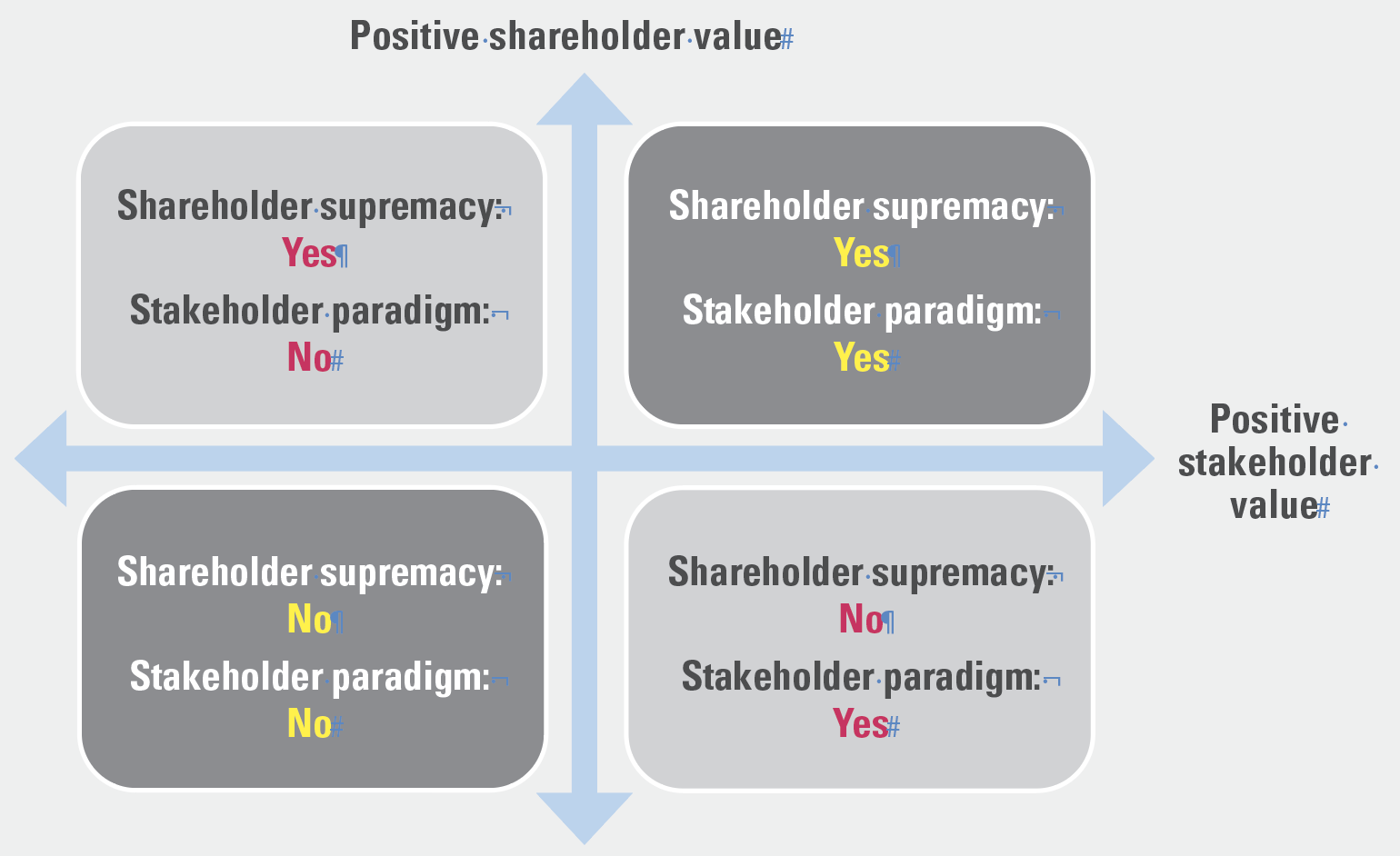

The following figure illustrates the shareholder primacy versus stakeholder paradigm conundrum. Everything above the horizontal (x-axis) line has positive shareholder value. Everything to the right of the vertical (y-axis) line has positive stakeholder value. In the upper-right quadrant and the lower-left quadrant (highlighted in green), there is no disagreement between the shareholder primacy and stakeholder paradigm viewpoints. In the upper-left quadrant and the lower-right quadrant (highlighted in orange), disagreement emerges between the shareholder primacy and stakeholder paradigm viewpoints.

The following figure illustrates the shareholder primacy versus stakeholder paradigm conundrum. Everything above the horizontal (x-axis) line has positive shareholder value. Everything to the right of the vertical (y-axis) line has positive stakeholder value. In the upper-right quadrant and the lower-left quadrant (highlighted in green), there is no disagreement between the shareholder primacy and stakeholder paradigm viewpoints. In the upper-left quadrant and the lower-right quadrant (highlighted in orange), disagreement emerges between the shareholder primacy and stakeholder paradigm viewpoints.

If most corporate projects fall in the two green quadrants, the traditional net present value rule for evaluating production, employment, marketing and R&D decisions would be fine. Consider the upper-right quadrant. This is the quadrant representing operational and human resource investments many U.S. corporations made during spring 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, 69% of the 100 largest U.S. corporations made drastic changes to their employee work schedules to safeguard employee health, according to a JUST Capital study. Sixty-four percent of these companies made significant changes to accommodate customer concerns about health safety and logistical convenience, and 62% increased the size and scope of their contributions to their communities. Alex Edmans, a finance professor at London Business School, provides a more comprehensive analysis and extensive empirical evidence supporting this argument in his book, Grow the Pie: How Great Companies Deliver Both Purpose and Profit.

The shareholder primacy versus stakeholder paradigm debate primarily involves the projects that fall in the orange quadrants. There are three systematic reasons for projects to fall in the upper-left or lower-right quadrants: lack of competitive product or labor markets, differential time horizons and differential risk exposures. The issues of differential time horizons and risk exposures can be solved by implementing managerial incentive compensation plans that align manager incentives with long-run shareholder value. For example, the incentive compensation of senior corporate executives could consist only of restricted equity (that is, restricted stock and restricted stock options). The compensation is restricted in the sense that the individual cannot sell the shares or exercise the options for one to two years after their last day in office.

Which problems should corporate directors try to solve?

- Directors' first order of business is to ensure management incentive compensation is focused on creating and sustaining long-term shareholder value.

- Directors may use their business judgment to allocate value to non-shareholder stakeholders if they believe that so doing will enhance long-term corporate business success and value. Also, in so doing, boards can and should consider reputational, legal and regulatory risks that could affect the business success of the corporation. Openness to all talent and concern for communities almost certainly serves shareholder interests as well as social justice.

- The Business Roundtable and other business leaders should reconsider their efforts to apply direct and indirect pressure on corporations to focus primarily on non-shareholder priorities. Because public corporations are more susceptible to such pressure, it could be an impetus to companies to go private or not go public. Fewer public companies leads to diminished support by the broader citizenry for corporate America, resulting in higher corporate taxes and increased regulation. Also, having fewer public companies can lead to more concentrated product markets, with the increased likelihood of diminished competition in these markets, resulting in collateral negative consequences on customers and employees.

- Climate change poses significant challenges for societies and businesses to reduce carbon in the atmosphere and adapt to evolving changes in surface temperatures. Corporate directors should press managers to disclose more information about the exposure of their long-term value to climate change, and corporations may act to reduce emissions and increase their adaptability in service of a focus on long-term value maximization. However, that step alone will not resolve climate change. Significant efforts to combat climate change require public policy shifts in the United States and abroad. Turning more to corporations simply because the political process seems broken and makes little progress won't do.

The modern corporation has been an enormously productive societal and organizational invention. The corporate objective of maximizing the company's long-term shareholder value, while conforming to applicable laws and regulations, is the genesis of the success of the modern corporation and its unprecedented record of improving humankind's welfare through job creation and wealth creation. That capitalism needs to be inclusive in its benefits is also true. But 50 years on, Friedman's shareholder primacy — long-run shareholder value maximization — remains the right place to start, even if it is not the end.

Sanjai Bhagat serves on The boards of Prolink, Integra Ventures and the National Association of Corporate Directors — Colorado. He is a professor of finance at the University of Colorado and author of Financial Crisis, Corporate Governance, and Bank Capital. Glenn Hubbard serves on the boards of ADP, BlackRock Fixed Income Funds and MetLife, where he is chair. He is a professor of economics and finance at Columbia University, and was chairman of the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush.