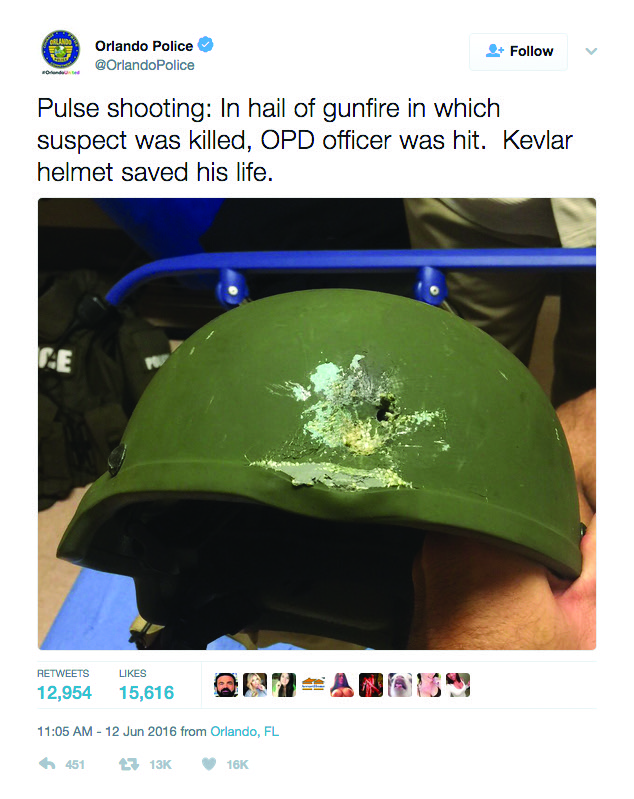

Would a product like Kevlar — DuPont's light-weight, super-strong fiber used in body armor that has saved thousands of lives — get to the marketplace today?

Research and development began in the mid-1960s on what became Kevlar; it wasn't introduced until 1971.

“No CEO in their right mind today would ever give approval for (research and development of) Kevlar,” explains Edgar S. Woolard Jr., who was CEO of DuPont from 1989 to 1995. A short-term orientation can make CEOs “afraid to make big decisions.”

For Woolard, a former director of Apple Computer who was instrumental in bringing Steve Jobs back to what is ranked as one of the world's most innovative companies, there's no question the short-term mindset can negatively impact the kinds of innovation that might change the world.

But now, it appears, many other business leaders are seeking to swing the pendulum away from the obsessive focus on short-term results to approaches designed to spark innovation and create value over the long term.

Boards in general seem to be paying more attention to long-term goals, says Ronald P. O'Hanley, chief executive of State Street Global Advisors, the investment management arm of State Street Corp., of which he is vice chairman.

He points to his own company as an example. At every board meeting questions are asked about the long term. For the capital plan, he adds, the long term is considered when discussing reinvestment, dividend policy and buybacks.

Resist short-term fixes

As leader of the world's largest asset management company, Larry Fink has a giant megaphone to crusade for a longer-term mindset in boardrooms and C-suites.

For the past several years, the CEO of BlackRock, which has $5.1 trillion in assets under management, has challenged top business leaders to resist the pressures of so-called quarterly capitalism that he believes threatens innovation, sustainable growth and the welfare of society. He has criticized (in letters to CEOs of leading companies in which BlackRock's clients are shareholders) the tendency for corporate leaders to reward investors through buybacks and dividend increases while underinvesting resources for the long term. He has reminded leaders that their duties of loyalty and care are to their companies and long-term owners, not every activist investor who owns stock at a moment in time.

Late last year, some prominent CEOs and directors publicly called for comprehensive solutions and policy changes to encourage reinvestment for the long haul. CEOs who agreed to endorse the American Prosperity Project, an Aspen Institute effort, include Paul Polman of Unilever, Ian C. Read of Pfizer, Charles V. Bergh of Levi Strauss and Phebe Novakovic of General Dynamics. Directors who signed on include Charles O. Holliday, chairman of Royal Dutch Shell and V. Janet Hill, director of Carlyle Group Management LLC.

Research backs up the belief that short-term orientations dominate at U.S. companies and exact an enormous cost on the economy. Nearly two-thirds of C-level executives and board members who responded to a 2015-2016 survey by McKinsey and Company said the pressure to deliver short-term results had increased in the past five years.

(See related article: Big Investors Short-Termism Drumbeat)

This short-term outlook has resulted in the loss of millions of jobs and trillions in GDP growth, according to a February report by McKinsey Global Institute in cooperation with FCLT Global. By contrast, the small number of companies that operate with a long-term approach deliver superior financial performance, the report says.

“It's like driving a car. Only focusing on quarterly results is like driving down the road and staring at the speedometer,” says Sarah Williamson, CEO of FCLT Global, an initiative begun by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board that is dedicated to developing tools and approaches that encourage long-term behaviors.

But while there's a widely-held sense that the balance is out of whack, there isn't a consensus about what the optimal level should be or how to achieve it, says Miguel Padro, senior program manager for the Aspen Institute Business & Society Program.

“Business and government leaders need to take this on for the good of society and the economy,” says William Lazonick, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell who has studied the subject.

Retain and reinvest

Before 1980, CEOs weren't as obsessed with maximizing shareholder value each quarter, Lazonick says. Instead, they were focused on using corporate resources for research and development.

“Through most of the 20th century, American corporations were governed under a system best described as ‘managerialism,' in which executives typically rose through the ranks at a single company and had as their primary objective the survival and growth of the corporation itself,” according to a 2015 Roosevelt Institute report titled “Ending Short-Termism.”

Management saw itself as balancing the interests of many ‘stakeholders,' including employees and customers, the report says.

This manager system became a powerful engine of economic growth, Lazonick notes.

“And through its retain-and-reinvest allocation regime, the managerial corporation contributed to greater employment stability and income equity than had been the case before the 1940s and would be case after the 1970s,” Lazonick wrote in a 2015 Brookings Institution article.

Shareholder revolt

By the 1980s, vocal shareholders began rising up against what they considered entrenched management. Before long, the belief that companies should “maximize shareholder value” held sway.

Changes in law and financial markets empowered shareholders to enforce demands on managers, the Roosevelt Institute report says.

One of the key demands was bigger payouts to shareholders, the report says. Before the 1970s, roughly half of profits made by American corporations were distributed to shareholders. The other half went to investment. Contrast that to the 1985-2015 period where an average 90% of reported profits were paid to shareholders. In some years, total payouts exceeded total profits. Nearly all the increase came from share repurchases, something rarely done by companies before the 1980s, the report says.

The short term use of cash or debt to buy back shares and drive up stock price comes at the expense of investment in the future, say advocates of sustainable capitalism.

Fixed capital investment by American corporations is at its lowest in 65 years despite record profits, the American Prosperity Project says. When it comes to investment in workers, skills training paid for by employers dropped 28 percent between 2001 and 2009.

“You can't play that (short-term) game because eventually you run out of gas,” Woolard says.

The long-term pay off

Companies ranked as long term outperform their peers on key financial and economic metrics, according to a new study by McKinsey Global in cooperation with FCLT Global.

The findings rest on the newly-created “corporate horizon index” that uses a data set of 615 large- and mid-cap publicly-traded companies from 2001 to 2015. Companies were identified as more short term the less they invest and the more they try to manage earnings, such as cost cutting to increase earnings rather than revenue growth, said Timothy Koller, a partner at McKinsey & Company. Companies were compared to companies in the same industry.

Revenue at companies classified as long term cumulatively grew 47% more on average from 2001 to 2014. Earnings cumulatively at these companies also increased 36% more on average in the same period, the report says.

Long-term companies on average spent nearly 50% more on research and development than other companies in the period and they continued to increase R&D spending during the financial crisis, the report says.

Market capitalization at the longer-term companies during this period grew $7 billion more on average than shorter-term peers. Finally, companies classified as long term added nearly 12,000 more jobs on average from 2001 to 2015, the report says.

But long-term firms were in the minority with only 164 ranked as long-term firms, or 27% of the sample. McKinsey and FCLT declined to name the 164 long-term companies. But in a February article in Harvard Business Review written by people involved in the study, Unilever, AT&T and Amazon were among those named as long-term companies.

Getting investors on board

There are concrete actions boards can take to implement long-term approaches.

When setting its long-term strategy, a board should be confident it's the right one for the company at that time, said Paul DeNicola, a managing director in PwC's Governance Insights Center.

Next, the company needs to engage large investors, including discussing the company capital allocation plan, how executive compensation is tied to performance and how the board composition is the right one to lead the strategy.

“Getting investors to buy into longer-term approaches to value creation truly starts in the boardroom,” says Carol SingletonSlade, head of U.S. Board Practices at Egon Zehnder, a leadership advisory services company.

It requires, she continues:

• Diligent agenda-setting at the highest level.

• Understanding that regulatory and compliance issues are priority agenda items.

• That boards must be much more deliberate and demanding of executives, coaching them on how to deliver the most pertinent, succinct data to present.

• Efficiently covering these pressing issues at the onset of meetings, which will ultimately leave more time to focus on strategy.

Once these longer-term strategies are set, the board must stand by the strategy, supporting the CEO through potential market changes or dips in performance.

“Trust and confidence,” she adds, “come from full engagement across the board and executive team, and investors will respond positively to this level of alignment.”

For their part, big investors are asking boards to communicate their long-term focus, says Glenn Booraem, a principal of Vanguard Group.

Still, achieving a better balance between short- and long-term approaches will take time. “It's going to be a while before we see real changes in both Corporate America and on the investment side,” McKinsey's Koller notes. ν

Maureen Milford is a Delaware business writer focused on corporation law and corporate governance matters.