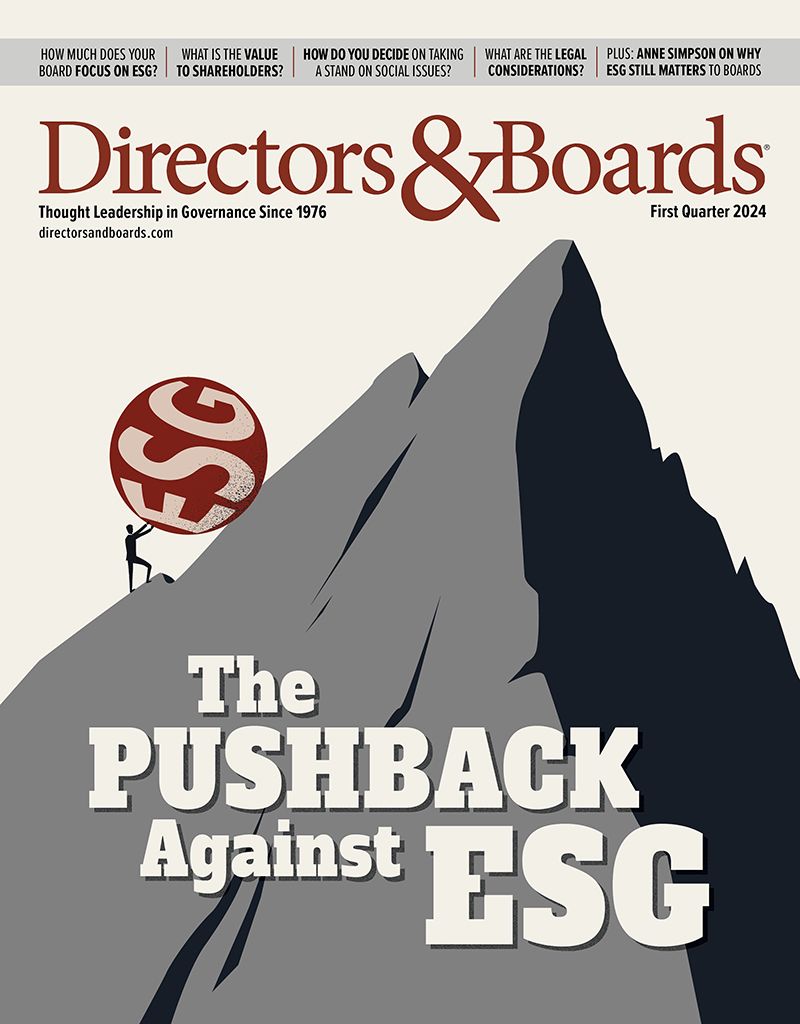

The world of corporate governance has changed dramatically in just the past two COVID-dominated years — and, frankly, not for the better. The original thrust of the 30-year governance movement focused on better board composition, independence, power and structure. This created dramatic and positive change in the functioning of most American public, private and non-profit enterprises. Today, however, that focus has shifted mainly to issues arising out of a newly dominant environmental and social movement, labeled “ESG” (where, sadly, the “G,” standing for governance, is positioned last).

The world of corporate governance has changed dramatically in just the past two COVID-dominated years — and, frankly, not for the better. The original thrust of the 30-year governance movement focused on better board composition, independence, power and structure. This created dramatic and positive change in the functioning of most American public, private and non-profit enterprises. Today, however, that focus has shifted mainly to issues arising out of a newly dominant environmental and social movement, labeled “ESG” (where, sadly, the “G,” standing for governance, is positioned last).Boards are now confronted with varied and serious demands for dramatic change in approach to their corporations' environmental and social responsibilities. The pages of both the popular financial press and the specialty governance publications are dominated by discussion of this issue. Longtime observers are left wondering where this new focus came from and what its implications are for the future of American business and investing.

There is nothing at all new with demands for corporate-focused environmental and social change. These concerns date back to the late 1960s, which was an era of significant social upheaval. Supporters of such change attempted to influence corporate policy in these areas through the extensive use of the shareholder proposal. They argued that there was a moral and social imperative for companies to support social change. The vast majority of investors, however, did not buy their arguments, and such proposals attracted little support.

By the mid-2000s, after noting the success of the corporate governance movement in effecting significant reform in board structure, based on the argument of the economic benefits of such changes, the environment/social activists smartly changed tack. They began to argue that progressive environmental and social policies would create better corporate results over the long term and dramatically enhance shareholder value. This met with slow but intensifying success. It was not that society had suddenly pivoted towards their position, but that influential members of the investing elite began to support their approach.

This movement dramatically accelerated when Blackrock's Larry Fink authored his now-legendary letters to the CEOs of various large-cap companies seeking support for “economically based” environmental and social change. Other financial leaders joined the charge, arguing that, in the absence of positive social change emanating from the national government, corporations needed to fill the void. Many of the largest institutional investors joined the movement, and suddenly “ES” was at the top of their voting and investment agendas.

Boards began to confront the important issues raised by the leading investment funds. In fact, in the last year, the board community has been overwhelmed with constant demands for progressive change in a number of areas. It is argued that the millennial population is nearly unilaterally supportive of this focus and that to remain economically relevant, Corporate America must adopt its approach to these issues.

This intense focus on environmental and social issues has dominated the board agenda at many public companies. Lost in the shuffle, however, seems to be meaningful attention paid to the actual “stuff” of the business itself. Less focus on the details of the business will mean real problems when a company, as all will do at some point, encounters a downturn. While many may disagree, the “E” and “S” are really luxuries in the overall operation of an enterprise, and if the business starts to flounder, attention to worthy externalities will have to take a back seat to immediate critical challenges.

The assumption that all millennials subscribe to the “ES” viewpoint, acting and thinking in unison, is just plain wrong. No human community is monolithic. Disparate viewpoints are common to all groups in our society, and it is unfair and inaccurate to prejudge an individual's philosophical bent based solely on their age. And, as we are all aware, viewpoints change with age.

As divided as our society is on these issues, so are the fund investors for whom the managers act as stewards. It is somewhat presumptuous to clothe one's own personal social goals in the mantle of economic advantage to justify a position opposed by many of one's own investors.

Focusing on the “G” in “ESG,” however, is something almost all of us can agree on and ultimately creates greater corporate accountability and value. A well-governed company will always attract bright and sensitive directors who will react appropriately to the important “E” and “S” issues before them. Ultimately, though, a good business is about providing superior goods or services at a fair price. When we lose sight of that goal, we all will be worse off, regardless of social positions.