Rising stakeholder expectations surrounding environmental, social and governance issues (ESG) are spilling into a growing corporate awareness of the need to address them. Though some companies have begun to demonstrate progress and commit to commendable goals on the issues — and make strides in integrating oversight at the board level — ESG has yet to become commonplace in executive compensation programs, seemingly the final step of solidifying corporate responsibility over the issues.

As corporations are increasingly seen as beholden to stakeholders beyond just shareholders, incorporation of ESG metrics in incentive programs represents an evolution towards substantiating this widening scope of responsibilities.

Despite the long-term nature of the issues, and where they exist today, ESG metrics are often found in annual incentive programs and are rarities in long-term programs. Although beginning to develop, companies currently lack confidence in their ability to define, measure and quantify the right ESG metrics to hold management accountable for their outcomes.

How should ESG metrics be meaningfully integrated into executive compensation programs? Here are some “thought starters” for boards:

Metric Selection

A crucial first step is metric selection, which depends first on defining which issues are most “material” to a given company. Determining these issues is outside the realm of compensation design. Here we assume the company has already defined material issues and set goals towards achieving them.

Annual Incentive Plans

One way to integrate ESG would be to emulate current approaches and add it to the annual incentive plan. This may be the preferred approach if the goals are truly short-term in nature or are easy to measure/ judge on an annual basis. There are three basic, common approaches:

Individual component: If a plan already has a measure of individual performance, ESG goals can be integrated into individual goals, providing the flexibility to tailor the goals to the executive most responsible for their achievement.

Scorecard: Metrics are also often added to a scorecard of goals, generally worth a collective 20%-30% of payout. This allows the flexibility to integrate qualitative and quantitative metrics, to combine ESG and other strategic goals, and promotes a sense of collective ownership. The danger with this approach is evident in the current market: too many goals on a scorecard — particularly qualitative goals — can dilute the incentive's impact. If added to a scorecard, only a few of the most critical goals should be included.

Discrete metric: One or more discrete measures could also be incorporated, as either standalone metrics or modifiers. Safety is often incorporated as a negative modifier; a data breach might be incorporated in a similar way. Discrete metrics are often eschewed given the difficulty of prioritizing a single goal, or of quantifying a single year's results. However, a number of companies already disclose meaningful, annual ESG-related goals such as Intel's commitment to reaching 90% compliance annually on each of 12 ESG supplier expectations. A similar method could be used for longer-term goals with annual milestones, perhaps around reducing energy usage, reducing waste, or offsetting emissions.

Long-Term Incentive Plans

Given the long timeframe of most ESG issues, long-term incentive plans seem a more intuitive mechanism to measure performance and drive the right behaviors. Why, then, have companies avoided this practice?

One challenge is identifying and quantifying the most material issues. Past those initial stages there are further challenges relating to structuring an incentive within a standard long-term incentive framework, which generally contain recurring, quantitative three-year goals.

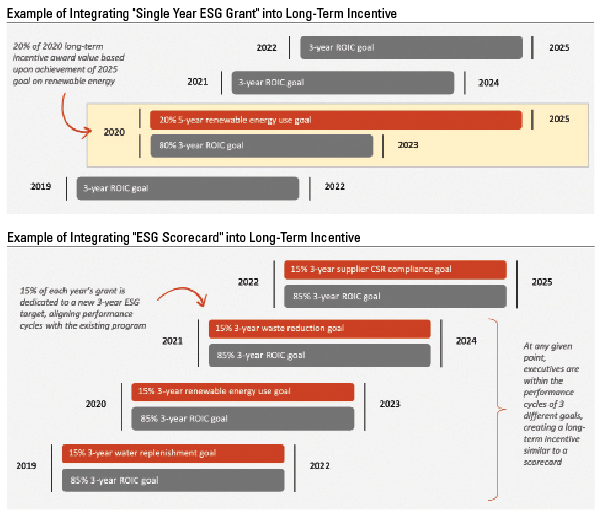

A variety of viable solutions might address these challenges. One is to carve out a portion of a single year's grant to be based on a given issue, allowing the flexibility to lengthen that portion's performance period to fit the goal's natural endpoint, which may better fit long-term goals without steady annual progress.

For example, PepsiCo has committed to replenishing 100% of the water used in manufacturing in high water-risk areas by 2025. For upcoming long-term grants, a meaningful portion (e.g., 20%) of the total value for each executive could be based on the 2025 goals. The award would likely vest at the end of the performance period, given the longer-than-usual timeframe, but as discussed below, may provide for early vesting opportunities upon early- or over-achievement.

These goals could also be attached as “kickers,” whereby significant overachievement leads to higher upside potential than existing metrics, or to boosted payouts for financial goal achievement.

For PepsiCo's water replenishment goal, overachievement might be timing-based, with a 2.0x payout if achieved two years early, 1.5x if one year. The possibility of early vesting may also incent the same behavior, for example, allowing executives to vest in a threshold payout (e.g., 50%) if a certain level is achieved by 2023 (e.g., 90% replenishment).

This design, however, suffers from the criticism of placing too much value on a single goal, when most companies have a number of equally important, long-term ESG goals. One potential solution would be to create a long-term “scorecard.”

For example, PepsiCo actually has five 2025 goals related to water use in high-risk water areas; target payout could be tied to achieving all five, with an above-target payout or early vesting if several goals are met early. A long-term “scorecard” could also be devised by setting a different long-term ESG goal each year, eventually focusing executives on achieving two to three material goals at any given point and allowing a natural evolution of long-term goals.

Looking ahead, in a world where companies and their boards believe that performance achieved in a socially and environmentally responsible way is the only way, executive incentives will evolve to reflect this reality. Some of the current barriers to including ESG metrics will fall away as companies and investors become more sophisticated about defining and measuring their key issues.

Thinking beyond current approaches for ESG metrics in incentive plans will be critical in ensuring future designs meet the longstanding objectives of incentive plans: to motivate and reward executives for strong results for the benefit of the corporation and its stakeholders.

Kathryn Neel is a managing director at Semler Brossy and leads the New York City office. Olivia Voorhis is a consultant with the firm and is also based in the New York Office. They can be reached at 212.393.4000 or kneel@semlerbrossy.com and ovoorhis@semlerbrossy.com